- Home

- Pavlos Matesis

The Daughter Page 9

The Daughter Read online

Page 9

The inside walls of her house were whitewashed, and the windows were narrow.

So we could see her clear as day, but bits at a time. Only glimpses of a huge black bat. Desperate to break free from its cage, she pounded against the walls, trying to find a way out. Like a huge, gawky, blind bird she was. But instead of flying towards the window, she kept crashing into the white walls.

At night she looked even larger, as the shadows looked bigger in the light of the acetylene lamp. The house was dark on the outside, and bright on the inside, besides the acetylene lamp, she put the electric lamp and the candles to burn, for her dead son to see better. She just didn’t want to close his eyes. We could see her, like a wild blackbird missing the windows, crashing into the walls, backing up and crashing into them yet again; and then she would climb up on to a table or a chair to catch her breath. Then her shadow would cover the whole ceiling, and after that she seemed to swoon and fall, we waited for her to come to, and then we caught sight of her again. Two whole days and nights we watched over her.

The first day we all stood there on the pavement across from her house and that night everybody crowded into our windows. The second night we forgot all about the curfew and, all of us women went out on to the pavement to mourn the fair lad, right outside her door. And inside she kept flitting back and forth like a bird trying to fly towards the light. The inside of her house brightly lit, and the front of it was darkest black. Nobody said a word to us about being out.

At dawn on the second day she came downstairs, opened the door and begged for food, she needed strength to keep up her lament. They gave her food, she ate, bolted the door again, and went back upstairs to mourn her son. We watched over her. Every so often one of us would have to leave for work, or to answer nature’s call, or to eat. Then someone else would take his place. Mrs Kanello left all her kids right in the middle of the pavement and went off to work. Don’t you budge, she told them, even if the Germans show up.

The Germans showed up. That evening it was. They stared at us, pretending to be puzzled. One of them stopped in front of Mother but before he could say a word she tells him in a soft voice, We’re watching over her. And pointed to the bat coming and going in the lighted windows, that was illegal too, the blackout was in force. Maybe he understood, maybe he didn’t, but he left, the German did. Laughed and went away.

On the third morning comes Father Dinos, scowling like an icon and all dressed up in his finest vestments, and shouts Chrysafina! Here’s where your dominion ends! And he broke down her door and carried the body away for burial. She followed along behind like a little girl, speechless.

There were a lot of us at the funeral. In the front of the church lay the dead man in an uncovered coffin, carefree now, his eyes still open, like a tiny rowing boat cutting its way through the waves without so much as a farewell for us. After the burial mother kissed Mrs Chrysafis’s hand and says, Don’t waste your tears, you’ll never get over it. Until you die. That was when some woman shouted, What’s that whore doing here? and Mother said, Forgive me, all of you, and took my hand and we left the cemetery. They didn’t put a cross over his grave; just a tiny little flag made from a white sheet of paper, with a blue cross painted on it. Beats me where they found the coloured pencil.

Every day Mrs Chrysafis went to the cemetery and ate a little earth from her son’s grave. That’s what we heard from Thanassakis, Anagnos’s kid, the school master from Vounaxos village. If you can imagine, the yellow-skinned kid would play right there, in the cemetery. Afterwards, we heard the same story from Theofilis the sacristan; saw her with his own eyes and being as he was a bit of a gossip he told Father Dinos, figured he shouldn’t be giving her communion. If I was in her shoes, I’d eat dirt, Theofilis, he said, so get the hell out of my sight and go and sweep out the church, tomorrow’s Sunday.

Subsequently, after the so-called Liberation it was, some partisans’ committee wanted to lay down a marble gravestone, like a kind of monument. But Mrs Chrysafis wouldn’t hear of it. All she wanted was to eat the earth from her dead son’s grave, a little at a time, just a pinch. Like holy communion, said Mrs Kanello. Kept it up even after UNRRA appeared on the scene. I don’t know what happened to her, but she was certainly still alive when we had the Junta; every three days she’d pay a visit to the cemetery, never moved to Athens, did Mrs Chrysafis. Time passed, and I lost track of her. As a matter of fact, it was Mlle Salome who asked after her, years later, when we met in some hick town near Grevena it was, and me on tour at the time. She wasn’t a ‘Mademoiselle’ any more as it turned out; now she was the wife of the biggest butcher in town. When I say ‘on tour’ you might get the idea I was the star. But at least I got some lines of my own, a whole half page of dialogue, in fact. The actress who was supposed to play the role got knocked up along the way, so they rang me; of course I did it on the cheap, extra’s pay, but when opportunity knocks, who’s going to spoil it by haggling? It was summer anyway; better than spending my holiday in the apartment.

So there we were, playing in Grevena, and nipping up to this nearby town for a quick show. I head for the local coffee-house. Nice town, know what I mean, I tell the owner (some town, the place was a run-down dead-end if I’ve ever seen one, but me, all my life I’ve been buttering up people to survive, and believe you me I’ve survived): anyway, the guy was so flattered – here’s an actress from Athens talking to him, after all – he wanted to stand me a spoonful of vanilla treacle, but what I was after was to keep my lipstick in his icebox. It was summertime and the damn thing was melting all over the place. I always let the village coffee-house owners fight it out for my favours; had to protect my lipstick, you know.

So there I am in this hick town near Grevena, back during the Papagos and Purefoy administration it was – you know, the field marshal and the ambassador – just after I nip over to the coffee-house to pick up my lipstick round about midday I say to myself, why not take a peek into the butcher’s, right next door, the habit stuck with me from the Occupation, butcher shops were romantic places back then. Across the street some men were taunting me in a highly unseemly fashion; forget them, I say to myself. In fact I’ll just hang around at bit longer, let them tease me; give my stock in the company a boost. So I turn my back on them – I was always more spectacular from behind – by then they were howling Hey look, it’s Raraou! they must have seen my name on the poster under my picture. I’m pretending to be eyeing some ox liver when all of a sudden I hear a woman’s voice from inside.

‘Why if it isn’t Roubini! Roubini? You are Roubini, aren’t you?’

It was Mlle Salome, of all people. Last time I saw her was that day during the Occupation when we were gathering snails under Deviljohn’s bridge and she drove by in the wood-burning jitney clutching a caryatid.

Lo and behold, there she sat at the cashier’s window in the butcher’s shop looking like Cleopatra sitting on the Sphinx, and behind her on the walls were pictures of the royal couple (the late and former, these days), and Christ. Next to them was a picture of an Alpine meadow full of woolly Merino sheep, an ad of some sort.

Mlle Salome was sleek and portly now, but I recognized her right off. Just imagine the hugs and kisses and the tears, why she even gave me two pounds of mince meat, plus she ran over to the coffee-house, got my lipstick and put it in the refrigerator where they kept the best cuts.

Remember, they were the ones who went on the lam from Rampartville just before the Germans sealed off the neighbourhood. Actually stole a goat with her own two hands, she did; they thought that was the reason. There was only one way to save themselves: take to the road. But Mlle Salome abandoned the troupe when they hit this particular town, eight months after the premiere. That was where the town butcher asked for her hand in marriage. What swept me away were his thigh cuts, that’s how she put it, and so I bade farewell to Art, she said, waving at the joints of meat hanging all around her.

She looked wonderful, even if she did have varicose veins. The butcher turn

ed out to be the ideal husband, worshipped her like a goddess, gave her two kiddies. Just in the nick of time, dear, she tells me, I was over thirty-eight but in the maternity hospital I gave my age as thirty-four, I know I was taking a chance, I say to myself, but I never told the invaders my age and I’m not about to change now. Better die in childbirth. But I made it! Two kids after forty. As she talked she kneaded the mince meat, her fingers were full of rings, she was a real princess now, thanks to that butcher of hers. That night they came to the show. Darling, you were born for the stage, she told me afterwards. Remember I always said so, back before the war even? Who gave you your first role, back then in Rampartville remember? Remember how hungry we were? I still miss it a little bit to tell you the sinful truth; my waist was as slim as a wasp’s, remember how I used to look?

Listen to that, Salome missing the hunger! I asked her about the rest of the Tiritomba family.

Well, to tell the truth, their last name wasn’t really Tiritomba. And they weren’t real stage people either. Salome was from Rampartville on her father’s side, the place across from ours was her family’s, she was even engaged, before the war that is. It just happened that her sister Mrs Adrianna married an entertainer, still, deep down she was a housewife. The guy was from Salonica, name of Zambakis Karakapitsalas. Married for love, mutually. He had a troupe of travelling players, even acted himself. People said he even used to have a dancing bear in the troupe, before Adrianna, that is.

So, this guy Zambakis Karakapitsalas had the most lavish sets and costumes of any road show.

Anyway, this opera company from Sicily goes bust in Salonica and Zambakis, who was a young man at the time, somehow scrapes together enough to buy the whole show, lock stock and barrel, even though it’s all opera leftovers. That’s how he made his name, putting on Cavalleria Rusticana or The Intrepid Albanian Maid with the same stage settings; in the Unknown Woman – get this – the chambermaid making her entrance in a broad-brimmed hat and petticoats. And the female lead in the Shepherd Lass of Granada appeared in Greek national costume along with lace gloves and parasol from La Dame aux Camélias (which he changed the title to Consumptive for Love). Well, you make do with what you got.

He and Mrs Adrianna made a perfect match from day one, except he was the jealous kind, wouldn’t let her out of his sight, even dragged her along on tour, the man was a bit of a hotblood. If you’re not here when I want you, I’ll do it with somebody else, he said, just as barefaced as that. But they lived happily, seeing as how Adrianna had a bit of the wanderlust herself, liked new places. Before the war in Albania (fight over a country like that? Big deal!) she visited 570 villages and towns on all her various tours, picked up some wonderful home-made dessert recipes along the way; Mrs Adrianna was just wild about cooking. Me on the stage and you at the stove. Zambakis was always telling her tenderly. They had a daughter, too. Fortunately for them, on account of two plays in their repertoire had little orphan girl roles, and Mrs Adrianna always blessed her child before she went on stage to play the orphan.

Hubby wouldn’t let her set foot on stage though, except to sweep up after the show. I want my wife to be an honest woman, the poor guy tells her. So she ran the wardrobe department: she was the one who mended Tosca’s or Marguerite the consumptive’s evening gowns, glued the sets for Nero’s palace back together when it got ripped in transit, and minded her husband in the bargain, particularly when he was playing a role where he had to wear a fustanella, she would un-eye him as a precautionary measure, and double-check to make sure he was wearing his drawers. Because one night the rogue slipped by her and suddenly there he was, dancing a folk dance in his fustanella with no drawers on, wanted to impress some young lady in the audience so it seems. That was when Mrs Adrianna whipped him for the first time. The first time, and the last time. No wonder, you’ll say, never gave her cause, never went on stage bare-bottomed again.

They reached Rampartville in October of 1940, late in the month, just a little before ‘No’ day, as luck would have it. They only had one work lined up. The Orphan’s Daughter. The daughter in question had to be five or six years old, so they announced a contest: all families with daughters were invited.

All the high-class mums with daughters took on seamstresses to get ready for the audition. But talk about good luck, that very same day Mlle Salome drops by to order tripe for her fiancé, takes one look at me. Diomedes, she says to my father, your daughter’s a natural for the role, let the kid do it – and pick up a few drachmas while she’s at it.

Next day she takes me to the cinema herself, the ‘Olympian’ it was called, and they picked me, unanimously; have to thank Mlle Salome, she was the first one to unearth my natural talents. They didn’t pick me just because I happened to be the tripe merchant’s daughter, no, they saw that inner spark of mine and that’s the story of how I got started on my future career.

So I played the part which put the high-society mums in one fine dither because some gutwasher’s kid beat out their precious little darlings, not to mention all the seamstress money. My part only lasted two minutes, no lines to speak either; I played this little girl whose mother was always beating her and sending her to her illegitimate mother-in-law and she, the mother-in-law, would send her right back again, anyway, generally speaking, they made a football out of me, right up to the final curtain.

The premiere, which took place on October 26th 1940, was my triumph. The audience, all high-society people, was relieved when they saw the kid getting slapped around and tossed to and fro like an old rag doll; that’s what my part was. And on account of how back then nobody played expressionistic, all the slaps were real naturalistic and my head was spinning and I was seeing double, not to mention them pitching me back and forth across the stage, but the leading lady wasn’t all that strong so I fell plop on to the floor like a ripe watermelon, and a cement floor it was too. But even then I didn’t let out a peep, not a tear; from that moment on, I was in it for the glory. Got paid, too, three drachmas for the premiere: probably to make sure I’d show up for the next performance. Of course I played the second night, got another three drachs, which I handed over to my mother, and that was how I entered the world of the Theatre.

On the twenty-sixth was the premiere, my moment of glory as the motherless child, and on the twenty-eighth the war breaks out, you’d have sworn somebody was out to sabotage me, artistically speaking. Zambakis, he’s called up on the spot and gets himself killed even before he reaches the front, kicked in the head by a mule and that was curtains, so to speak; end of career. And us, as a nation, we have to go and say that cursed ‘No’, just to spoil my future. Anyway, fatherland comes first, even if you can’t see it.

Mlle Salome’s future was futzed with that ‘No’ of Mr Metaxas’, he was prime minister back then, God curse the ground that covers him: there. I’ll say it, even though I am a nationalist. That’s when her fiancé leaves for the front. Scared out of his wits and miserable, but her fiancé all the same. Not that she really wanted him; the whole thing was Mrs Kanello’s doing, August 15th it was the day they torpedoed the armoured cruiser Elli. The wedding date was set for October 28th, after the last performance. Mrs Kanello liked playing the matchmaker; even today she’s always harping on the matter, but you won’t catch me getting involved in any love match, not on your life.

So the moment he hears the declaration of war on the coffee-house radio, Mr Fiancé dashes off to enlist, primarily he was deserting, actually, running out on love. Snuck out of town, he did, so not even his fiancée could catch a glimpse of him. Actually, it was really Mrs Kanello he was afraid of, afraid she would beat him and force him to get married, right then and there, at the railway station.

Not too much later Mlle Salome gets a card from the front and shows it all around, just as proud as she can be. Loaned him to the nation, was how she put it. What are you so proud of? says Mrs Kanello, believe you me, I have to crawl on all fours to set you up and now you go lending him out, the nation is better than you,

that’s what you’re saying?

Kept his picture on her dresser, Mlle Salome did; during the Occupation she would kind of look sideways at it and say, His face reminds me of somebody, but who? Us too, his face reminded us of somebody, impossible to say who.

Until one fine day during the Occupation, Mrs Adrianna’s daughter Marina goes and draws a moustache on the fiancé’s photo, just to annoy Salome. Mrs Adrianna takes one look and goes, Holy Christ and Blessed Virgin! She shows the photo to Mrs Kanello and she goes, Holy Christ and Blessed Virgin! all this time, and we never noticed! They muster all their courage and show Salome the photo, but just as she’s about to sigh with longing, she gets a good look at it and goes, Holy Christ and Blessed Virgin, why, he’s the spitting image of Hitler.

That’s when we realized just who the fiancé reminded us of. Aye, so that’s why the Germans show you all so much respect when they search your house, says Mrs Kanello.

From that moment on Mlle Salome put him out of her heart once and for all, like a true patriot. Recovered from the complex she got when her fiancé stopped writing after the first postcard (we never found out whether he ever came back, nobody ever heard a word about him, down to this day). But she goes over to Kanello’s and says, Pay me back for the engagement rings, dear. That’s how we found out Mlle Salome bought the rings out of her own pocket. And she went back to her knitting, making sweaters for the partisans.

After Mrs Adrianna’s husband died – by then the Occupation was settling in for the long haul – she says to herself, That’s all for the artist’s life and the tour we’ll live and die right here in Rampartville, in our family home. Now she was a forty-year-old housework with an eighteen-year-old daughter and her sister Salome unmarried and almost-married, and the main thing in her mind was how would they survive and what would they have to eat. So Mrs Adrianna calls all her relatives, meaning her brother Tassis. He’s the one who had the little jitney, before the war he did the run between Rampartville and a couple of villages up in the mountains, full of scrub oak, goats and now partisans. He converted the jitney to a wood-burner. But business was slow; real slow.

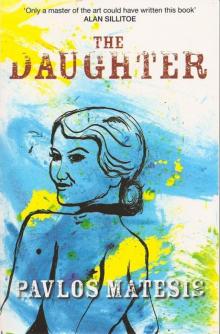

The Daughter

The Daughter