- Home

- Pavlos Matesis

The Daughter Page 18

The Daughter Read online

Page 18

When you get right down to it, the main reason she didn’t want to go with the cripple was because when she heard people talking about ‘love’ or ‘bed’ it meant nothing to her. Used to titillate her when she was a little girl. But after she was twelve or thirteen, she had never known the desires of the flesh. And when she happened to think to herself, which didn’t happen all that often, why she had no taste for this thing, why she had no urge, no desire, up from her memory would rise the image of herself as a little girl standing there outside the church of Saint Kyriaki along with Fanis, her brother, playing games, the two of them, hide-and-seek mostly, to keep warm and to dry the rain on their clothes, until Signor Alfio had finished and left the house, then little Roubini could scurry back home and shake off the raindrops. And mostly help her mother empty the basin and set the table for dinner, the Italian was an interruption in their daily schedule, a delay.

And so it was that never once did the desire to touch a man’s body overcome her.

But that hardly worried her. She kept it hidden in any event, considering it ill-suited for a future star of the stage. Not that she didn’t have opportunities, but she never once had the desire to caress a man’s body. Sleeping with her mother at night, that gave her pleasure. The only thing that disturbed her was the lack of a toilet. She had arranged a crude, temporary one outside the back wall of the blockhouse; she dug a hole, set up a wooden crate upside down over it, cut a circular opening in the top and surrounded it with a cardboard partition; that was where they looked after their daily needs. In fact, she trained her body so she only needed to use it at night, after dark, even though there were no neighbours to spy on her.

She felt no humiliation in begging, first because she had neither approved the idea or even chosen it. Second, it was only a temporary solution, until the pension came through, until they could sell their house in the provinces. What’s more, she found out all about Athens, learned how to sing and handle tough situations in front of the public, learned how to bow; in fact, she had lots to show from begging.

Won’t come across, the little bag of bones, mused the cripple. But he wasn’t hot for her. Still, if she did put out, at least it would be free. He liked the mute more. But one morning when he tried to reach his hand under her dress when the two women were getting him dressed, the girl tipped the cart on its side, the cripple toppled over and fell on his side on to the cement floor. The mother stood there staring straight ahead. The cripple lay there on one arm, like a stump. Then the girl grabbed the bridle rope from the cart and lashed him across the face. Then she took yesterday’s earnings and walked over to the corner where the cripple hid his money, he had no idea the girl knew his hiding place. Right before his very eyes, staring straight at him, she took his savings, dressed her mother and out they walked, the two of them.

First they dropped by a woman’s from their home town, lived in a blockhouse just like they did, but she’d fixed up her place. This woman crocheted lace, which she sold from door to door. When Raraou and her mum came calling, she brewed them a cup of coffee. Then mother and daughter went off.

They took the bus downtown, first stop was their MP’s office. Then the daughter took her mother sightseeing, to all the attractions, the royal palace, the works. Afterwards she treated her to a French pastry. And while they were at the pastry shop, they nipped down to the toilets to primp themselves like human beings for a change. The mother didn’t want to go at first, Raraou almost had to drag her, Don’t be afraid, she said, we paid good money. After that she bought shoes for her mother, a butcher’s knife, a dog chain and a small sack of cement. And that was how Raraou spent the cripple’s stash. Then they went home (that’s what they called their blockhouse now) on the bus. They found the cripple as they’d left him, lying on his side atop his arm, in a puddle of piss.

They cleaned him up, covered him with blankets and prepared him a meal. When Raraou took him his plate she said, Listen, no-legs. I spent your money, every last drachma. Don’t you ever touch my mother again, see. Bought me a butcher’s knife and some cement. And she showed him them. If you ever try and touch her again I’ll mix up the cement and I’ll stick the knife in your belly, and as soon as you open your mouth to yell I’ll plug it full of cement. And we’ll walk out. And the cement will set right in your mouth and you won’t be able to yell and you’ll die alone, you’ll rot right there where you sit. It’s not us who need you, it’s you who need us. So if you know what’s good for you, you’d better mind your p’s and q’s and show us some respect.

From then on the cripple treated them respectfully. Still, every night before they turned in Raraou would lock one end of the chain around the legless man’s wrist and the other to a leg of their bed. And she slept peacefully, there beside her mother. In the morning, she would release him. He didn’t like it of course, but what was he supposed to do? She threatened to have her MP call the police to throw him out. But the cripple didn’t want to have anything to do with the police, especially since he claimed to be a hero of the Albanian campaign, in addition to begging without a government permit. He’d lost his legs in an accident, poaching fish with dynamite. So he let Raraou have her way. When you get right down to it, he was pretty well off; he had two slaves, and he’d begun to salt his profits away again, things couldn’t be better.

He didn’t try to touch the two women again. Better share the living space and work together, he reasoned.

What really impressed him was how strong the mother was going up hill. She wrapped the rope around her chest, lunged into the harness, and towed him along like a mare threshing wheat. At night the daughter massaged her shoulders, and rubbed fat into the rope burns on her chest and arms. One day, the mother stole a wad of cotton batting from a shop where they’d gone to beg for money for the disabled hero, and that night she took the batting and some old rags and made a kind of harness which she wore right next to her skin, under her dress, when she towed the cripple’s cart. The daughter was delighted, What a wonderful mum I have, Mum, what a great idea! she shouted.

Not far from their place was a graveyard. Raraou jumped over the wall and pulled out a couple of wooden crosses and loaded them on to the cart beside the cripple, and that solved the problem of firewood for the brazier. It got a bit smoky of course, but the warmth helped cut down on the dampness.

Raraou hid the butcher’s knife and the bag of cement where the cripple would never find them. And come summer, after she finished cleaning him up, helped him on to his pallet and brought him his meal, Raraou went off for her first acting lessons. On the way she dropped her mother off at their neighbour’s, the lady with the lace doilies, and strolled on down the hill, to the group of houses which was getting larger all the time, why, they even had an outdoor cinema. Raraou would scramble up the wall, or up a nearby tree and watch the stars gliding to and fro across the silver screen. Those were her acting lessons. Greek films, those were her favourites. Afterwards, she would pick up her mother and the two of them would stroll home. Her mother enjoyed those little social calls, since her neighbour was so busy with her knitting she hardly said a word. The mute woman helped her with the household chores, did the sweeping, you name it, and then sat there and listened as the lady of the house talked about her house back in the provinces, about her neighbours. She’d managed to get electricity which meant they had plenty of light, and the time passed pleasantly. One day, on their way back home, Raraou told her mother, See, mum, Mrs Fanny hasn’t put up one photo of Aphrodite. Not of her husband either.

The take was good, at public markets mainly. There were always lots of people in a hurry, housewives for the most part. Raraou set up the cart so that it blocked their way, what were the good ladies to do? How could anyone who was a true Christian, a believer in the Last Judgment, walk past a half-man and a deaf-mute woman without giving something, some money or a piece of fruit from her shopping basket.

Later on, when Roubini began her theatrical career as Raraou, she came to know almost every sm

all town in Greece with travelling theatrical companies. Gigs were always easy for her to find, since she worked at half-price; in addition to onstage extra, she would also do odd jobs and run errands for the impresario, which meant she got lots of work. The other actors considered her a petty stool pigeon. Later, when she’d finally bought her own apartment, she told her mother that the time they’d spent begging with the cripple had given her the inner strength she needed to face an audience. More important, she learned not to let people hurt her, not to feel shame, shame is for provincials, she told her mum. But she also respected her obligations. There was this certain Mrs Salome in Grevena she always sent her best wishes to. Mum, she said, Salome’s the one that discovered my talent. Salome showed me how to live, thanks to her I know how to live, theatre-wise. But begging taught me how to live better. That saying I remember from school, she said.

From fellow actors to stage directors, everybody admitted she had a kind of presence, even if she always seemed to end up in a nervous collapse which meant she wouldn’t be hired for the next season. Plus she had a reputation for being trouble, not to mention her two fits on stage, on tour, how did she expect an impresario to go running off at night to find the village doctor, it wasn’t his obligation, and furthermore, he was of no mind to pay the doctor bills; so they gave her two or three brandies to calm her down, and the show would go on. But come the following season she wouldn’t get the call. By then, of course, she had her father’s pension, her own apartment, her radio, stereo, records and, when you get right down to it, she was proud of her condition. It was sort of aristocratic, nerves, none of those tumours and gynaecological things any woman can come down with. The kind of illness that made her feel like a big city girl.

Her performance really picked up when the cripple bought a radio. It was the kind that fitted into your hand, ran on batteries. That meant Raraou could do musical numbers; she began to enjoy her begging act even more.

Summer was their toughest season. The cripple had put on weight thanks to all the good treatment, now he really weighed a ton. Pushing the cart was humiliating, too, how were two women drenched in sweat supposed to beg cheerfully, all soaking wet? Especially Raraou who had to perform her number before they brought out the tin cup. What’s more, the customers began to thin out.

Summer was hard on Raraou, she’d got into the habit of fainting at noon in the bazaar, and the cripple had to whip her with a green stick to bring her around. Twice her mother collapsed, also.

One day in July, at two o’clock, the cripple fell asleep in the sun, with his hand stretched out. Raraou propped up his back with the two boards and pulled her mother over into the shade to rest. The market place was empty, it might as well have been the desert.

I’ll just rest for a bit and then I’ll try and find an ice-cream man, she told her mother. And she leaned back against the wall and fell into a deep sleep. Before her eyes closed they looked at the cripple sitting there plump and sleek, sweating in the heat of the sun, his hand stretched out for alms, fast asleep, and suddenly she hated him, and wished for his death. But at that exact moment sleep overcame her and she began to dream. She dreamed the cripple was dead.

The burial was in progress. It was late afternoon, the light was soft and diffuse, the heat of the day had abated. Flowers were blooming in neat little rows on a green-grassy hillock. The sky was a deep blue. And Raraou was looking at the funeral as if it were a brightly coloured picture, with a blue-sky background. The cripple was laid out on a wooden pallet, without a mattress; candles burned at each corner, but the flames were invisible in the sunlight. The cripple’s hands were folded in the proper fashion, a wedding wreath on his head; he was wearing a jacket. And he was whole, his legs joined to his body, patent leather shoes on his feet. The funeral psalm droned on. At his head stood the Gypsy who begged alongside the main road every day, and next to him stood his dancing bear. The bear was standing on his hind legs, holding a censer in his paw, and swinging the censer back and forth.

Just a few steps behind the bear stands Roubini’s mother. But Roubini is not part of the picture; she is outside the dream.

The psalm ends, the Gypsy makes the sign of the cross over the dead body, Ashes to ashes, dust to dust he says, he’s ready to go. Here, the last kiss. What can she write on the cross, Raraou wonders; but suddenly it hits her: nobody knows the cripple’s name. He never told them, they never asked. And as she mulls it over, her mother steps forward. Wait just a moment, she says. Her mother is speaking. But it’s only a dream and Raraou is not amazed that her Ma can speak; not in the slightest. Her ma moves forward, up to the edge of the pallet. Her ma pulls at the cripple’s shoes. The lower part of his body snaps off and falls to the ground; his legs are made of wood.

‘He wanted those legs so bad,’ her mother says, turning to the bear. ‘I rented ’em. Paid 2,000.’

And she hoists the wooden legs on to her shoulder.

The sun evaporates, vanishes. Raraou snaps awake to the shouts and curses of the cripple. Why is there that smell of incense, who was chanting? Then the heat floods over Raraou again and she starts calling out in a loud voice, hawking her wares, Step right up! Right this way, ladies and gentlemen, yours for only 2,000 (later they chopped off the three zeros and the thousand-spot turned into one drachma). The cripple is terrified, her ma tries to drag her away, but it’s still too early, the shops haven’t opened for the afternoon. And at the far end of the street there’s a fire burning right in the middle of the road. How can we pass, Raraou thinks, it’s impossible, we’ll never get by, but they decide to leave because the three of them are thirsty and their water bottle is empty and her ma suddenly stiffens and her eyes roll back in their sockets and she collapses. Raraou fans her, slaps her on the face. The cripple wheels his cart over, pulls her by the skirt, and hands her a bottle, Drink, he says. Raraou stares, stares at him. What’s that? she says.

‘Elixir,’ he answers. ‘Take some, I stole it a couple of days ago from that pharmacy, took it from the bench, give her a slug.’

‘What is it?’ asks Raraou.

‘How should I know. For sure it’s medicine, it’s bound to help her.’

Raraou shakes the bottle; liquid, she says to herself Let’s give her some to drink instead of water. She takes out the stopper and tries to open her mother’s mouth; nothing, her teeth are clenched tight. So she stuffs the neck of the bottle into the side of her ma’s mouth, her ma starts choking, but she comes to, fortunately. Raraou takes a sip of the elixir.

‘Give me some too,’ says the cripple.

She hands him the bottle, he takes a mouthful, Bitter, he says. Let’s get out of here, maybe we can find a café open, cool off a bit.

They start up the hill. Fortunately the fire has stopped. Raraou loops the rope over her shoulder, holds her mother’s hand and they move forward effortlessly, why, if I only had a scene like that to play in the movies, she thinks, I’d show them what it takes to be a star. Now she says ‘movies’ instead of ‘motion pictures’.

They move forward, the heat as intense as ever, her ma has recovered, but Raraou is holding her tightly by the hand as they start their way up the slope. Everything is closed tight, the corner café too and the cripple damns the heat, damns it’s mother, come on, he says, we’ll ask for water at some open window.

The houses are all one-storey affairs with two stairs, scraggly mulberry trees in front, shutters closed tight. One of the houses, the one there at the corner has its shutters open, someone’s standing there. Let’s knock, says the cripple. They advance cautiously lest the cart squeak, two caryatids look down on them from high atop the tile roof; the window is open, someone is watching them from inside, motionless.

Raraou is about to say ‘kind sir’ in a low voice, the window is in deep shade and the man inside is motionless, eyeing them. Perhaps he’s been watching them all this time. Raraou leaves the cart, goes up to the window with the open bottle, says ‘good day’ and is about to ask for water. She raises h

er eyes to speak; the man looking at them is a statue, a statue of a man’s bust standing on the windowsill. She goes back to the cart and they continue on. The cripple picks up a stone from his cart and flings it at the window as they go by.

‘How come you’re stoning the place, no-legs? We don’t even know them,’ says Raraou.

Now they’re going downhill for a bit. And her ma is feeling better.

She lets go of the rope and moves behind to guide the cart by the handles.

‘I told you never call me no-legs, skag,’ he says. And he picks up another stone from the cart, throws it and hits her ma in the back. Raraou sees, comes to a stop, brakes the cart to a halt, then lashes the cripple with the rope, without a word. He tries to protect himself but Raraou lashes him, weeping wordlessly, in a trance. The cripple starts shouting, Police, help, police! Then Raraou releases the chocks, the cart starts moving, picks up speed, rams into a wall and stops. Now the cripple says nothing. Raraou goes over to him.

‘How’d you like that? Want some more?’ she says.

But he says nothing, her mum is waiting further down the street, Raraou grabs the handles of the cart and they move off again, this time towards the fish market. Her mother is staring straight ahead. Whenever they have an argument her mother stares straight ahead, as if she were gazing out over a valley full of birds and flowers.

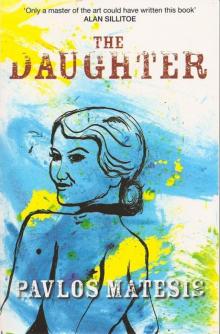

The Daughter

The Daughter