- Home

- Pavlos Matesis

The Daughter Page 16

The Daughter Read online

Page 16

Meanwhile, Doc Manolaras was getting set to go into politics, which is the reason why he was pulling strings to get us a pension. Politics was starting up again, you see, and the politicians were beating the bushes for votes. From us he stood to collect six, two from my father’s parents and four from us, counting our big brother Sotiris. Why, Doc Manolaras even promised to find him, saying, Asimina, I’ll leave no stone unturned to find your eldest and bring him back to you, no vote can escape me. Never did find our Sotiris though, but he did get a voter’s registration book issued in his name, which he used himself.

Still, the X-men didn’t give us trouble, even though plenty of families started leaving Rampartville due to their beliefs. Rampartville was a nationalist town, and everybody knew just who the left-wingers were. And when the X-men started their beatings and breaking down doors, plenty of people made up their minds to move to Athens once and for all, for shelter. That’s when Aphrodite’s ma left. Fortunately for her, because she got ahead. If you take away that they slaughtered her husband in those December Events, or whatever they call them, she’s doing just fine today with her lace doilies. Really has the knack, she does.

Funny thing, back then, there was this X-man, the sentimental type and a travelling greengrocer by trade, and he goes and falls in love with Ma. Her hair was a bit longer, styled it à la garçon I did, looked real good on her. So, late at night on his donkey he came by, most likely on his way back from the countryside where he went to buy his vegetables, he hung around behind the church singing songs full of meaning, like If you turn your back on the past or the hit of the day, I’ll take you away with me, only he changed the words to say he would take her away to other lands where they had a king and queen. Other times he sang patriotic hymns, things like Sofia-Moscow is our dream, but they came out sounding like a hesitation waltz.

This same greengrocer, he even put in a good word for Mrs Chrysafis. Another X-man comes right up to her door and tells her to her face that they’re going to dig up her son’s corpse, they’re not going to give that stinking commie a moment’s peace. But the greengrocer had a word with him and he left her alone. Not that Mrs Chrysafis cared a hoot: Go on, dig him up, she tells the X-man, and give me a call so I can see what he looks like now. Everybody’s nerves were pretty much on edge.

People in the neighbourhood were starting to talk about the love-sick greengrocer, but it was all a big misunderstanding. One day Mrs Fanny comes up to me and says, Roubini, get it over with, girl, either tell him Yes, or get rid of him. I was speechless. Mrs Kanello was telling me the same thing, got it all wrong for the first time in her life. No, I tell them, the greengrocer’s making eyes at my ma, what could he see in me? But I said it without really believing it, seeing as by then my breasts were coming out and I was getting taller.

But the greengrocer wouldn’t give up. One evening, in fact, while he’s serenading right beside our window, the donkey starts braying, and his master starts kicking the poor creature. Shut up, he hisses; my heart sank to see him tormenting the animal. It was a neat and tidy little donkey, come to think of it, with a little crown hung right under its forelock. Finally Mrs Kanello takes matters into her own hands, she buttonholes the guy and asks him what are his intentions towards the orphan, meaning me, the dimwit. That’s when everybody realized that it was Ma the royalist greengrocer was after. But soon after Mrs Kanello’s efforts he disappeared for good, and I could only think about what would become of the donkey, maybe he would beat it again.

She was always sticking her nose into everything and standing up to everybody, Mrs Kanello was. And nobody dared lay a finger on her even if everybody and his brother knew by now how thick she was with the Resistance and the partisans all along. Meanwhile we got our first letter from Mrs Fanny; it was addressed to Mrs Kanello, but it was for all of us. Didn’t ask a soul to tend the little candle on her daughter’s grave. All she said was there were plenty of empty – or emptied – houses in Athens. Also that there were blockhouses and they were all made from a new kind of material, concrete it was called, never wore out, and if you moved into one nobody asked any questions, particularly after the uprising. Didn’t make it clear what uprising she was talking about or if she was living in a blockhouse herself, sent us all her best and announced that her husband had been killed. The details we learned later, when we made it to Athens ourselves.

That letter of hers, it gave me inspiration: I made up my mind to head for Athens. In fact, the minute Doc Manolaras gives me his word he’ll look after Fanis for the rest of his life I say to myself, Roubini, I say, time to spread your wings.

Seeing as even from before the war, from back when the Tiritombas used me as a kick-ball on stage, I had this dream of the artiste’s life, of being an actress. That’s my main quarrel with the Axis and the Occupation, the main reason I condemn them is because I wanted to take off as an artist and they wouldn’t let me. And now it was starting to look as though my dreams would come true.

Artistic dreams, they can’t flower in the provinces. Put together the public humiliation, Ma’s condition, the encouraging housing news, plus Doc Manolaras who would be looking after Fanis, everything seemed to be pushing me to see myself as a future Athenian.

Ma’s condition gave me this problem. I mean, how are you supposed to enjoy yourself evenings keeping company with somebody who can’t talk? A couple of times I put on a little stage number for her, something I picked up from Mrs Adrianna, but Mother, she didn’t laugh. Plus in addition people made nasty remarks about her, even if they didn’t throw stones any more. I found out about it later from Mrs Adrianna, but what was I supposed to do? Take her out for a stroll or go to the movies? Impossible, after the public humiliation. Now it wasn’t only honest women made fun of her; even the other collaborators, women from good families who could pay to get out of the public humiliation, they started throwing things at her. Even one of the houses I fixed up work for her, they kicked her out, saying she was a collaborator.

That particular house, it had three daughters, the Xiroudis family it was. The place was always swarming with Italians, seeing as the father couldn’t budge from his chair since before the war and the mother had a taste for social climbing. When he heard Italians coming up the wooden stairs (really squeaky, they were) from his room, the father shouted, Sluts, that’s all you are, don’t you have any respect for your country? to hell with the lot of you. And you, what do you want with these whores of mine, you Italian bastards? And the mother stepped out on to the landing and said, Now now dear, calm down, the girls need a little amusement.

The Xiroudis family owned olive trees, lots of them; big money. Their cellar was full of jars of olive oil, big as a man. When I was working at their place, lots of times Mrs Xiroudis gave me the oil can and a funnel and sent me off to the cellar for a refill. I climbed up on a stool, uncovered the jar and ladled out the oil. More than once I fished a drowned mouse out of the jar along with the oil. Don’t breathe a word to the girls, Mrs Xiroudis told me. They’re so touchy, they’ll turn their noses up at the food.

When the people’s government committee started rounding up collaborators for the public humiliation, Mrs Xiroudis hustled her daughters down to the basement and stuck them into full oil jars, covered the top of each jar with a lambskin with holes punched in it so the girls wouldn’t die of asphyxiation, and tied down the lambskins with a rope around the neck of the jar. And that’s how she saved her daughters from the public humiliation; the committee came to take them away, searched the house top to bottom but couldn’t find them, so the truck went away empty-handed, my mother was already standing there on the truck-bed with a handful of other women, they started with the lower-class women. At night she tiptoed down and gave them water through a funnel.

Three days and three nights the three Xiroudis daughters stayed there, up to their necks in olive oil. How that affected the olive oil, it revolts me to say. Still, they escaped the public humiliation. And as for the oil, well, later their father,

the old fart, he sold it to the army, not to mention what he donated to the Partisan Fund, nearly fifty kilos of the stuff. Just think what our brave soldiers on the field of battle were eating mixed in with their olive oil, so be it, nobody ever died of polluted food, no matter what the scientists say.

The whole story we got from Victoria their housemaid a couple weeks later: they were beating her, so she happily told us everything. Victoria was no stranger to the Italians either; her mistresses handled the officers, she looked after the stable-boys. The day the British landed she packed all her belongings into a little satchel and at ten o’clock one morning she stood outside her master’s front door and began insulting them, Rotten traitors, bitches. That’s when she brought up the oil jars, how they made her eat food cooked with pissy oil (what else she said, even more gross, I won’t say: might make me sick to my stomach). After she said her piece she set off on foot for the port, how she got it into her head that Liberation equals marriage proposal and the Brits would take her away on their ships to their country and marry her, I’ll never know.

Three whole days Victoria waited there on the pier (beats me where she relieved herself) and singing ‘It’s a long way to Tipperary’. Finally, when she gave up on the Brits she hiked back to Rampartville beating her breasts and braying, No good double-crossing allies. Finally, with some help from Mrs Adrianna, they sent her back to her village with a truckload of unsheared lambs. I haven’t heard a word on the subject of Victoria ever since.

When the dust settled a bit, Mrs Xiroudis hung out a British flag like everyone else and fired my mother as housekeeper. Unfortunately you’re a collaborator Mrs Asimina, she told her. And those cold-fish daughters of hers had already taken up with Brits, fortunately the old man had croaked meanwhile, so he couldn’t keep up his raving against the Allies too.

Me, I never held a grudge against the Xiroudis daughters, just thinking of them doing their business in the olive oil three days and nights, I forgave them. But the other houses started telling Mother they really didn’t need her, seeing as now everybody was against the Italians and praising the Allies and liberty. So I had to drop out of night school so we could get by, now that Mother was out of work.

One evening I come home and I see the table set and beside my plate I see our big brother Sotiris’s ration book. Mother put it there. Now our ration books were nothing but souvenirs, there was no more soup kitchen, soup kitchens were for enslaved nations and now we were free and supreme among the victorious.

Next night when we sat down to eat there were four table settings, the fourth plate was at Sotiris’ place. She puts a serving on the plate, with bread and all. Fanis and I look at each other but we don’t say a word. Who was I supposed to talk to, anyway? Mother was learning to live with her dumbness. Fanis, the only thing he was worried about was that crushed hand of his, and me, I didn’t want to discuss it with the lady neighbours. I was head of the household now.

The routine with Sotiris’s plate lasted for almost a month, complete with a chair and everything. Then finally one night before dinner I get up, take the plate and empty it into the sink, quite a luxury you’ll say, but for me, it was waste I had to make. I wash the plate, put it back in the plate-rack, and after we finish our meal Fanis looks Ma in the eye and says, pure coincidence it was. He’s probably in Athens by now, Sotiris is. And goes outside to play.

That was his first hint that maybe we should be moving out.

Then came the trouble with the roof. In one corner the tiles were cracked from a couple of near misses from mortar shells, but we only noticed it when the first rains came. Adrianna’s brother Tassis brought his ladder over, climbed up and laid a sheet of muslin over the split tiles and set rocks at each corner to keep the whole contraption in place, a fine job he did, hardly leaked at all inside any more.

Besides the hole in the roof, the other thing that was pushing me towards Athens was Fanis. Everybody called him ‘The mute’s boy’ or ‘Fanis the whore’s boy’. Not that they meant any harm. That’s just what they called him, kind of a last name, just like Venus de Milo, for example. But our little boy was almost grown up now – has hair on his face the rascal – and now he was just wasting away, because of his hand. He made out it didn’t matter, and kept smiling though. Say he tried to show some temper when people called him names, or wanted to fight back, well, he always took it right on the chin and everybody knocked him down.

Plus in addition, I thought to myself, maybe in Athens we can find doctors to look at Mother, maybe scientists in the capital can bring her voice back. But my dream never came true. Those Athenian doctors, they never did find a cure.

We had to make up our minds, the roof was leaking again, Mrs Adrianna was always giving me encouragement: You were born for the stage; Kotopouli might be a half-decent actress but is she any prettier? I’ll give you letters of recommendation for theatrical companies, you’ll see all of Greece, she said.

Meantime Doc Manolaras, bless his soul, took on Fanis to work his country estate. It was land he bought on one of the Aegean islands. Later people said the land used to belong to a big Collaborator then the Allies confiscated it and Doc Manolaras bought it for a crust of bread, with title deeds and all. I don’t know a thing about titles and deeds but there’s one thing I do know, our Fanis is still working there, to this very day, and that’s where he’ll end his days, fortunately.

Once I didn’t have the boy to worry about, I made my decision. My ally was Doc Manolaras; moved up to Athens for good in the meantime, he had, and now he was hard at work bringing his voters to the capital, had to get elected in another district, you see, in Athens. Set up a kind of private moving agency, was what he did, when you come right down to it. Got Tassis appointed to the Anglo-Hellenic Information Service, and rented this half-car half-truck for him. This particular vehicle was always heading back to Athens empty, and returning with a load of material for the Service. So Doc Manolaras made sure it was loaded with voters who wanted to move to Athens, along with all their furniture, free of charge. That’s the way we went ourselves, finally. What’s more, Doc Manolaras made the rounds of his supporters’ homes in the evenings, it was all unofficial of course, promising a free house if a family had more than five votes. On account of those troubles, those December events, Athens was full of empty houses. Every family with less than five votes he set up up in an empty blockhouse, there were blockhouses to spare and no taxes to pay. Appears he also looked after Mrs Fanny, even if she wouldn’t admit she lived in a blockhouse; but later on all she could do was boast how she took over the place all by herself. She was a proud woman and she didn’t want to admit she gave him her voter’s book, or that Manolaras took out a book in the name of her slaughtered husband and now the late lamented partisan was voting for the nationalist slate ten years after they slaughtered him like a heifer that December in Athens.

Goodbye provinces, for everybody. That much good we got out of the Liberation and the hunt for lefties. Seeing as now they were lumping us lower-class collaborators in with the lefties, and the nationalist X-men would go after the both of us. For me, getting dumped in the same category as the lefties was as big a disgrace as Ma’s public humiliation. Whether I used to knit sweaters for the partisans or not. I always respected the partisans, but I never knew they were leftists, too.

It wasn’t long before we got our first letter from Fanis. He was doing just fine, the estate was full of fruit he could pick and eat to his heart’s content and he didn’t even have to ask permission, plus there was a beach not far away. He was supervisor, had a shotgun even. His advice was that we should leave. And he wrote he was only going to write to us again if he got sick; so long as he’s healthy he won’t be writing and if we don’t hear from him not to worry but if anything happened to us we should write him. And in the meantime, he’ll send us his best every time our member of parliament Doc Manolaras would go to the island on business. And we should send him our best the same way and keep him posted if we change our a

ddress, if we move to Athens was what he really meant.

I discussed it with Ma, I mean, what was there to discuss; me talking and her listening, didn’t even shake her head yes or no. Had to arrange for all our belongings, sell the house, part of her dowry it was. Some house, you’ll say, with a dirt floor and a scrap of muslin over the hole in the roof; who wants to buy the place?

What I mean is, that’s how it looked to me back then. Just imagine what it looks like today! Now there’s this huge apartment house, makes the church look like a chicken coop. So I hear, that is. And I’m thinking, My poor little pullet, how can you bear it with a huge building sitting right on top of you, my poor baby.

That’s how I bought my apartment. Back then I couldn’t even dream of such comfort. Anyway. I’ll see that it gets sold, Doc Manolaras tells me, in a couple of years it’ll be worth more bless his soul. We gave him power of attorney, picked us up in his car, drove us over to the notary and Ma put down her signature See, I say to her, good thing we taught you to write, look how handy it comes in.

We said our farewells to the neighbours, to Mrs Kanello, to the Tiritombas: I stopped off at the houses where I used to work and paid my respects and a couple of them gave me a tip, then Tassis and Mrs Kanello’s kids all pitched in and we packed our household belongings into bundles and loaded everything into Tassis’s vehicle, the bundles, the furniture, and Mother sat down right in the middle, with Mrs Kanello’s scarf over her head, didn’t shed a tear or blink an eye. Didn’t even turn her head as the car turned the corner and she left Rampartville for ever. And when we were clear of town, she tossed her head, undid the scarf and tossed it out the window, a pricy item like that! and let her hair blow free in the wind.

A little before we left I went into the house; it was stark naked and spotless. All swept and dusted, top to bottom, it was my way of showing my respect for all these years that house respected us, after all. I went over to the corner where my little garden used to be, my little pullet’s grave was nothing but a hole in the ground now. I spoke to her, I’m leaving, I said. But I won’t forget you. But you listen to me, do your best to melt into the ground, because it won’t be long before the machines come to dig you up. Now farewell; I will never forget you.

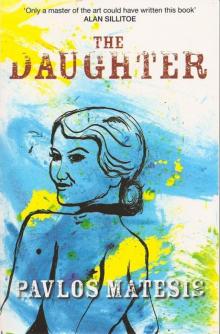

The Daughter

The Daughter